IN HIS FIRST AUSTRALIAN SOLO EXHIBITION, THE ARGENTINIAN ARTIST CONFRONTS THE EXISTENTIAL CHALLENGES FACING HUMANITY WITH BOLDNESS AND BEAUTY.

BY LOUISE MARTIN-CHEW

In formulating his vision for the future, Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno looks to the past. Inspired by the synergies and understandings that humanity possessed thousands of years ago, when lives were more attuned to the cycles of nature, Saraceno’s work elucidates how traditions of harmonious living are more relevant than ever—despite their low profile in a fast, technologically driven world.

Saraceno’s broad range of work encompasses large-scale installations, real-world experimentation, activism and participation in international events such as last year’s COP26. He describes his central interest as being “dialogue with forms of life and life-forming,” which has seen ongoing artistic and even scientific inquiry into the phenomenon of flight, the lives of spiders and their webs, and the capacities of natural forces such as air, thermal rhythms and the sun.

Much of his artistic work and creative experimentation, conducted at his sizeable Berlin-based studio, has been in the pursuit of flight without fossil fuels. An ongoing interest in kiting (or ballooning) spiders—which create parachutes of gossamer silk to catch updrafts and drift through the jet stream to propel themselves between locations—is made manifest in his beautiful, often immersive large-scale installations of web-like structures. Such micro interests inform larger investigations.

Over more than 15 years, the artist has produced a series of prototypes for solar- and wind-powered balloon flight. The most high profile example is his work Aerocene Pacha, in which Saraceno successfully flew a fully solar-powered hot air balloon over Argentina’s Salinas Grandes for 81 minutes, breaking numerous world records with the World Air Sports Federation for altitude, distance and duration of such a flight.

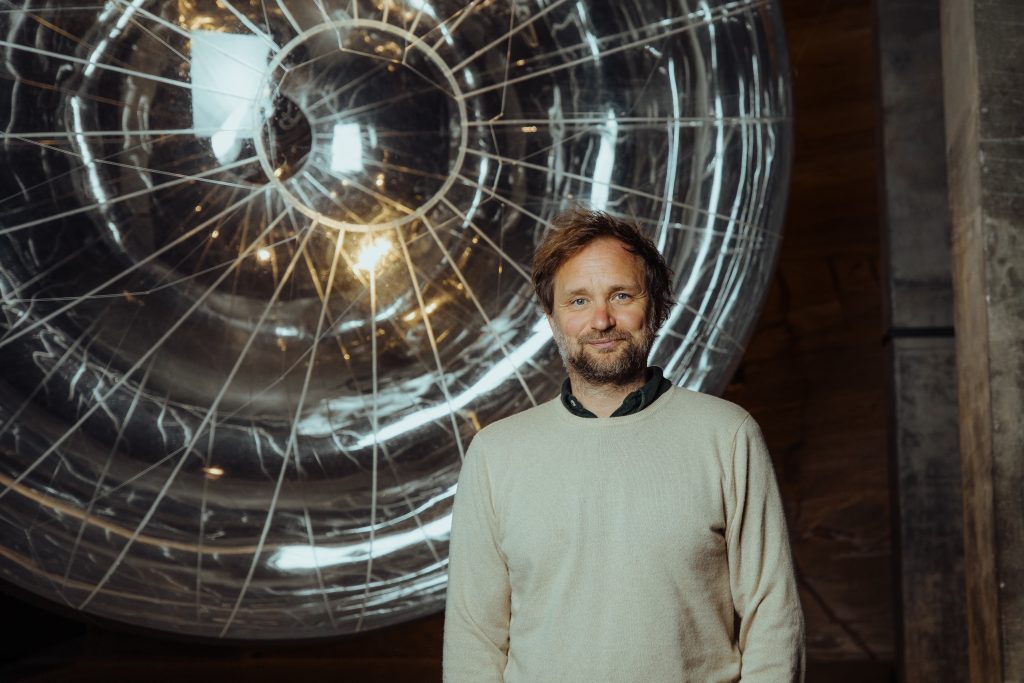

Saraceno’s curiosity is insatiable. He dares audiences to imagine a radically different future—yet there is nothing strident about his approach. We sit talking in the central hall of Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), beneath the floating canopy of giant air-filled spheres he has created for the institution’s major group exhibition, AIR. They drift with ease and elegance above us, gently bumping their mirrored surfaces as they circulate the space.

He is in Australia for this and another exhibition: Oceans of Air at MONA—his first Australian solo. Both are timely opportunities to consider the vitality of our shared atmosphere. His work Drift:

A cosmic web of thermodynamic rhythms (2022) seeks to activate our awareness of the transformative potential of that atmosphere. “Air belongs to everyone,” says Saraceno, “and we need to get it back.”

Saraceno was born in San Miguel de Tucumán in northern Argentina, but his family fled the country during unrest in 1976, seeking asylum in Italy and returning home a decade later. He went on to study architecture in Buenos Aires, before moving to Frankfurt in 2001 to attend Städelschule, an experimental art academy.

One of his earliest big breaks as an artist was his inclusion in the 2009 Venice Biennale, in which he created Galaxies Forming Along Filaments, Like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider’s Web, a series of impressive floor-to-ceiling webs made from black rope.

In his life and work Saraceno (pictured right) is driven to make a difference, to advance knowledge, and to explore possibilities.

He is preoccupied with the ecological degradation caused by climate change. “The world is falling apart,” he says. “All I can do is try.” He believes real change requires a shift from what he terms the “Capitolocene” (a dominant, exploitative model of carbon-driven capitalism, an “epoch of eco-suicide” in existence since 1945) to the “Aerocene”. The Aerocene vision—one he shares with other artists, researchers and scientists—removes hierarchies in favour of equality, participative actions, co-creation and collaborative practices.

The spheres above us at GOMA float thanks to their construction from two different lightweight materials that Saraceno and his team have developed, inspired by materials used in sustainable flight technologies. Their construction includes a mirrored section that deflects radiation from the sun while a second transparent area, designed to contain and maintain temperatures inside the sphere, allows floatation without fossil fuels, “powered only by the thermodynamics of the planet” Saraceno explains. These sculptures, the first of the artist’s indoor installations to echo the construction of his aerosolar balloons, move in response to changes in air temperature caused by audience bodies as they enter the space.

I ask him if an understanding of physics informs his interest in flight. “Maybe physics and science could learn from the arts,” he says. “Sometimes we could learn together, maybe. The knowledge that is locked within certain forms of knowledge does not help to transcend the possibilities of that discipline. It’s going to be lost in their own world.”

This tendency to break down barriers, work with different philosophical paradigms and foster a growing community of like-minded practitioners and people is central to his work. “Slowly, [my work is] hopefully allowing more and more people to experience the ability to float with the rivers of the wind or from the bottom of the ocean of air, in a much safer relationship with the world.”

Indeed, part of GOMA’s AIR exhibition is a Saraceno flight-starter kit that theoretically allows individuals to launch their own aerosolar sculpture. The kit hangs on the wall, components attached to a silver mirrored cross, including sensors so that its pilot may add measurements of humidity, air pressure and other atmospheric data to the Aerocene community’s collective climate action. This democratisation of the atmosphere is necessary, Saraceno says, because “the air is so often militarised and divided… we need to bridge this form of knowledge, to form these alliances.”

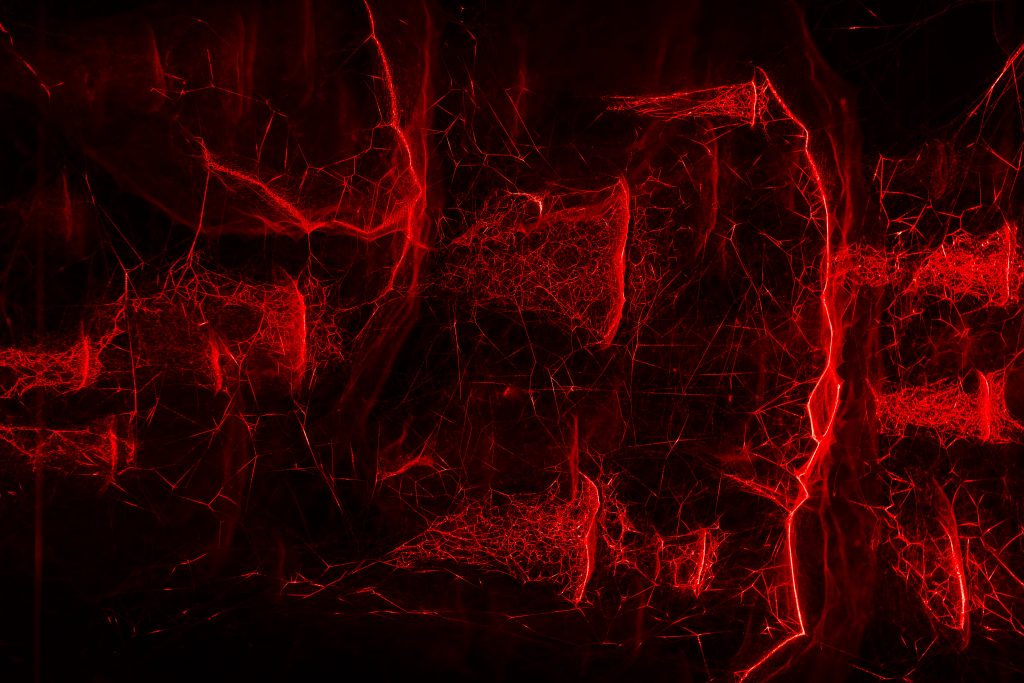

Such collaborations with the natural world are also central to Saraceno’s MONA exhibition. Oceans of Air calls for the acceleration of environmental action on earth, in its atmosphere and beyond. During previous visits to Lutruwita (Tasmania), Saraceno saw caves inhabited by spiders who emerge only at night, fuelling his long-held interest in spiders and spider webs. Extensive web installations are a key feature of the exhibition.

In a subterranean exhibition space, with dark rooms both spooky and fanciful, spiders and their light-as-air webs build on Saraceno’s ongoing international community research project, Arachnophilia. Here, intricate hybrid webs form “a material memory and diagram of the spider’s drift through the air” to become a poetic paean to old and new ways of living in the world.

Leaves from the fagus (Nothofagus gunnii), Tasmania’s only native deciduous tree, smoked by the Palawa people (local Traditional Owners), also feature in the exhibition, along with charts measuring air quality from all over the world; graphic illustrations of the demographic inequity in our collective atmospheres from Mumbai to Geelong. The charts challenge assumptions about the benign nature of air with the data translated as circles, shaded to describe air quality. As Saraceno relates, those most affected by climate change across the globe are also those who are least responsible for the extreme situation in which we find ourselves.

Such works are both arresting in their aesthetic finesse and urgent in their messaging. “I’m inspired by people who are living in a different way,” Saraceno explains. “I’m going to Argentina to meet again a community who, like many Aboriginal communities here in Australia, live in a very different way to how I’m living.” He wants to learn and draw from these different rhythms of life.

Art is rarely at the forefront of the debate about the way to achieve a better world, but Saraceno believes that beauty is required to inspire changes in attitudes. “We need to be seduced to allow ourselves urgency,” he says. His work revives the idea that the realm of artists extends beyond the studio or the gallery into the real world.

Air is central to shifting the regimes of inequity so entrenched in 21st-century societies. Oceans of Air, in its content and message, has the potential to promote a sense of shared responsibility.

As Saraceno notes, “not all have the right to breathe, and not all breathe the same air”—but we all should. In our journey toward new climate realities, visions like Saraceno’s may be crucial in inspiring—both metaphorically and literally—a necessary shift in the air.

Oceans of Air is showing at MONA until 23 July.