By Anna Snoekstra

Acclaimed Iranian-Australian photographer Hoda Afshar on art in service of life, activism, and the camera as an active participant in her vast and varied career.

When it came time to name her major exhibition for The Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Iranian-born, Melbourne based photographer Hoda Afshar struggled. How to find a title that would hold so many different projects under its umbrella?

The exhibition covers 19 years of work; images and video that range from black and white documentary-style photographs of illegal bathhouses in Iran, to Warhol-esque hyper-coloured studio shots littered with pop culture iconography. Afshar found the words in a line from Iranian-American poet Kaveh Akbar’s poem Milk, which read: ‘a curve is a straight line broken at all its points so much / of being alive is breaking’. “I changed and shortened it to A Curve is a Broken Line,” Afshar says. “It captures vulnerability and resilience at the same time, which are qualities I try to capture in all my works, especially the ones that are about different communities and other people’s stories.”

Afshar’s most recent work, In Turn, isn’t about other people—it is supremely personal. Commissioned by AGNSW for A Curve is a Broken Line, it explores her experience of watching the Iranian uprising from afar, a moment shared by many Iranian women living abroad. When Afshar and I speak, she’s clearly exhausted. It’s five in the afternoon on a Friday and she’s been rushing from one commitment to the next in the lead-up to the exhibition opening. But when she speaks about the creation of these photos, her whole demeanour changes; her gesticulation animates, and her face lights up.

The photographs feature women standing in front of blank skies, braiding each other’s hair and holding white doves. Hair braiding is a statement of resistance, linked to the feminist movement in Kurdistan and also rooted in Black American history and Asian cultures. Afshar wanted to acknowledge the universal aspects of this as well as the specificity to the images coming out of Iran, where women are coming together to protest for their right to choose whether or not to wear the veil. The uprising was sparked by the brutal death in custody of 22-year-old Masa Ahmini

shortly after she was arrested by Tehran’s ‘morality police’ for being in public without a hijab.

“A lot of people don’t know the visual language that comes into the images you see coming from Iran, the performance of the body, and the fight for freedom, and the unity between the women who wear the hijab and those that don’t,” Afshar explains. “You see them on the streets of Iran. The woman with the hijab is plaiting a woman’s hair that is refusing to wear it. [The women are] documenting all of this for the gaze of an audience; they know that people are looking.”

It was harrowing for Afshar to witness the courage of those protesting across Iran from afar. Norway-based non-profit Iran Human Rights (IHR), which is tracking the protests, said in April that Iranian security forces had killed more than 500 people in their crackdown. Afshar tells me about the restlessness of this time. She was glued to her phone, wanting to be there to fight with her people as well as connecting and sharing information with the Iranian diaspora here in Australia to explore ways to raise awareness.

“As someone who grew up in Iran, I knew the level of courage it takes for people to do what they were doing,” Afshar says.

“It was inspiring, moving and very emotional, and it was giving us all hope. But at the same time, the excessive killing and violence by the Iranian government that was performed in front of the world’s eyes was bringing mourning and despair. The contrast between hope and despair was at the heart of that period for me and I wanted to capture that.”

The images themselves are like visual poems, with symbols exploring these conflicting emotions. The women braiding each other’s hair signify resilience and mutual care. The white doves are a symbol of grief and anguish, as in Iran, white doves were released into the sky for every protester death. Afshar shot the series on an old large-format four-by-five camera, the type of which is typically only used in a controlled studio setting. She attended workshops to learn how to use it. The images took a long time to create, with Afshar taking them from under a blanket while the subjects held the poses. The trained doves were another variable, as was the harsh, wet, and windy weather. Rather than resisting these volatile factors in her images, Afshar embraces them. “There’s this element of chance and accident that comes into the work. The camera has its own personality and characteristics that you cannot control fully.”

This tension between the staged and the documented has become an essential part of Afshar’s work. Looking back at her teenage years in Tehran sheds some light on these preoccupations. She was initially interested in becoming an actress, but fell in love with photography the moment she created her first image for a high school class. “I went to a park near my house, and I photographed a water fountain. When we developed our films at school, I remember the excitement I felt in the darkroom when I saw [the image] in the red light appearing on the paper. It’s a cliche story of a photographer, that you fall in love with the magic of the darkroom, but I was so happy. I don’t think I’d ever felt that happy.” Still, her first choice for university was theatre, but she didn’t get in. Photography was her second choice. “I spent a lot of time hanging out with the theatre students and documenting their plays. In fact, everything I’ve been doing with my photography is a form of staging reality and performing reality.”

Afshar grew up next door to well known Iranian photojournalist Kaveh Kazemi, who documented the events leading up to the 1979 Iranian Revolution and

its aftermath, as well as other conflicts across the world. While Afshar was studying, Kazemi took her under his wing, introducing her to foreign war photographers when they came to Tehran. She was initially focused on the documentary genre and at university, was taught to approach her subject objectively as a way of finding truth. But this methodology didn’t sit right. “You treat everything like an object, basically, and I couldn’t do that. I unconsciously was against the idea.”

Afshar made a series of photographs of Tehran’s illegal underground parties, later titled Scene. She didn’t want to take photographs of her friends without their knowledge, even though she understood that by telling them, they’d be performing for the camera. Instead, they became active participants, collaborators. Afshar didn’t tell her teachers that the images were staged, for fear of failing the course. It made her feel like she was cheating. “Years later,” she recalls, “I realised that what I [then considered] cheating was the methodology that I wanted to consciously use. I started believing in the process, and I made it bolder and louder and I openly spoke about it.”

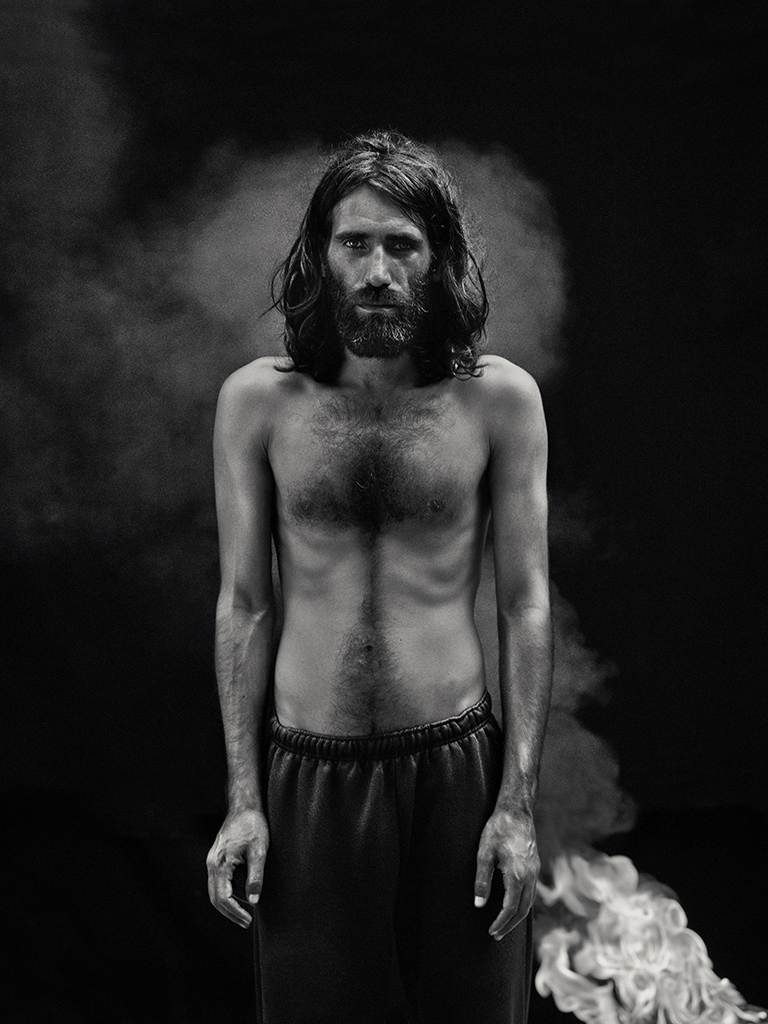

In both approaches, the interaction between life and art is fundamental. “There’s a famous saying that life is more important than art,” she says. “For me, art should be at the service of life. I would say it’s a form of activism. I have developed trust in the power of beauty and in the language of art contributing to change by drawing people in and making them ask certain questions. It’s hard to make people engage with something; they need to feel something.” Afshar believes art has the capacity to move the viewer past sympathy towards indignation and the need to act. Taken from her well-known 2018 series Remain, Afshar’s Bowness Photography Prize-winning portrait of Kurdish-Iranian journalist and refugee Behrouz Boochani cemented her belief in the potential of art as activism. She travelled to Manus Island to capture the photographs and made short films of the stateless men living there in detention under Australia’s immigration policies, including Boochani. “It was one of the most surreal experiences of my life,” she remembers. “Even when I was standing there, I couldn’t believe that I was there. Making the work that we made together in those conditions, and the trust that those individuals put in the work, still to this day, every time I think about it, it brings tears to my eyes.

“But the noise that that work made, made me believe that art has a lot more power than I thought it had. It made me trust it even more.”

As Afshar told me, she wanted to highlight the vulnerability and resilience in her work when choosing the title for A Curve is a Broken Line. Pairing that with the interplay of artistic inquiry and activism that drives her, and the mix of documentation and staging, she has created a body of work that is powerful but not always loud. The hushed courage of In Turn quietly manifests these dissonant concerns, and it’s beautiful.

Hoda Afshar’s A Curve is a Broken Line will be on display at The Art Gallery of New South Wales until 21 January 2024.