By Tyson Stelzer

Shifts in the global economy and local market, climate change, and the complexities of the French taxation system are all placing pressure on Champagne’s little family estates. But as many growers transition away from their own production, others are strengthening and expanding.

In the epicentre of the graceful slopes of Champagne’s fabled Côte des Blancs, there is perhaps no grower more privileged than the Péters family. Located in Le Mesnil-sur-Oger—the grand cru village more revered than any other—this estate is the proud custodian of a monumental 20 hectares of chardonnay spanning 60 vineyards. Six generations of the same family have tended these vines, and the estate has bottled its own champagne since 1919. Current custodian Rodolphe Péters has a rockstar reputation in the world of champagne growers. Yet, he has observed a fundamental and disconcerting change in his world.

“We’ve had 15 to 20 years of the golden age of weather, which has increased the average quality of champagne, enabling the growers to achieve success and producers from lesser and even obscure villages to emerge,” Péters tells me as we taste a grand cru chardonnay from his cellar.

“In the past, it was much easier to make consistently good wine in the grand crus, so many of the growers became lazy, and producers in average villages were able to produce more interesting wines from lesser vineyards,” he explains. “But since 2016, when the weather turned, it was the end of this game. It was easy when we could pick good vintages in most years, but now it looks like we are back to just two or three good vintages each decade. The young gun growers have never experienced this, so it’s not going to be easy for them forever.”

The rise of the grower-producer has revolutionised this generation in Champagne. Recent decades have seen the little guy step forward to demonstrate that top champagne is no longer the exclusive realm of the big houses and the famous names. Champagne is not just oceanic blends from everywhere but single villages and individual vineyards, tended, crafted, matured, and presented lovingly to the world by the same pair of hands.

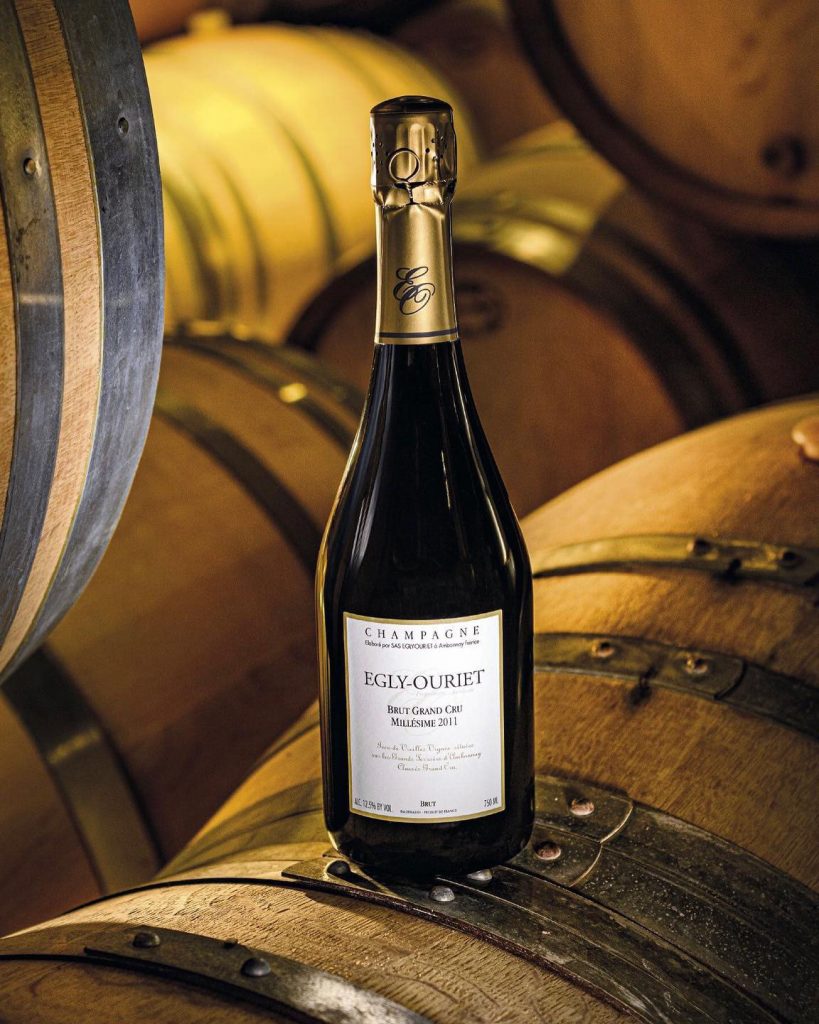

The champagne world has embraced top growers like Egly-Ouriet and Jacques Selosse, and prices have soared accordingly. But the dynamic is changing. One small grower told me in 2018 that he expected the next decade in Champagne to look very different, and that it will “not be possible for many of the small brands to survive”. He continues the struggle to sustain his own family business in a highly respected premier cru on the Montagne de Reims, but many others have given up.

In 2022, 37 grower-producers followed a growing trend and closed down production to instead sell their grapes to other brands. In 2008 there were more than 4600 grower-producers. Now there are fewer than 3700. Back then, growers sold 78.5 million bottles, almost one-quarter of all champagne production. Last year, this figure dropped to just 58.1 million, less than 18 per cent.

“The problem is that the French market is tough and very competitive,” says Maxime Toubart, president of Champagne’s winegrower’s union. “Vineyards are increasingly dependent on the houses to sell their stocks. Because [the houses] have the means to sell the bottles in distant markets at high prices, they can afford to pay a lot for the grapes.”

Nicolas Chiquet, of respected grower-producer Gaston Chiquet in the village of Dizy, agrees. “Every year, we are losing sales to the big houses,” he says. Chiquet is fortunate to be among the minority with global distribution. “Outside of France, we have less competition, and we have distribution through agents who are passionate about pushing growers. But in France, we are alone; it is more difficult, and we have to work harder.”

Péters believes there has also been a change in how grower-producers are viewed in those international markets. “In mature markets like the US, there was once a time when growers equated to top quality in the minds of consumers, journalists and sommeliers, so they imported something like 400 or 500 different growers,” he says. “And then they realised that it’s not because it’s a grower that it’s good, so now they are back to 350 growers.”

This scenario coincides with the retirement of many founders who produced their own grower champagnes for the first time.

At the same time, Champagne’s large houses are seeking to increase production to meet global demand and are eager to actively engage growers to shore up supply. As the next generation takes over, many are recognising that strong grape prices and high demand for quality fruit from these négociant houses presents a more stable and compelling business opportunity. Champagne pays its growers the highest grape price in the world, now up more than 80 per cent on the price 15 years ago.

Former Veuve Clicquot chef de cave Dominique Demarville has been working on facilitating relationships between growers and champagne houses for some 20 years, and he says he’s noticing a shift in the ambitions of new growers. “We are creating a new generation of growers who don’t necessarily want to sell bottles but who want to be top growers and sell their fruit to the leading houses,” he says. “In the next 10 years, 35 per cent of growers will retire, and most will lease or sell their vines to other growers.”

This critical shift in grower champagnes has been amplified not only by economic forces but by the harrowing extremes of climate change. The vagaries of Champagne’s marginal climate and the diversity of its microclimates have long dictated a wine style dependent upon blending multiple vintages, varieties and crus. Ever-more dramatic extremes are taking their toll, and yields suffered bitterly in 2016 and even more in 2017 and 2021.

Benoît Gouez, chef de cave of Moët & Chandon, points out that this is another area in which smaller producers are disadvantaged. “A small grower in one village has nothing to compensate for difficult weather,” he says. “Grower wines are very good, but by nature, the quality of champagne is uneven. The more grapes you can access, the more you can be consistent.”

Champagne’s average grower now owns less than 0.7 hectares. In a good harvest, this would facilitate production of just 7000 bottles. Larger growers are naturally more likely to bottle their own champagnes, but the average production of Champagne’s 3690 growers is a mere 15,800 bottles.

As vineyards are increasingly divided through inheritance, owners are forced to seek employment elsewhere. For Charles Heidsieck chef de cave Cyril Brun, this inevitably leads to a decline in producers’ ability to navigate the volatility of the work.

“We have observed that with the new generation, sometimes they have lost the soul of a vigneron,” he says.

“They lose involvement with the technical side of viticulture; not so important in an easy harvest, but critical in vintages like 2018.”

Jérôme Prévost is one of Champagne’s most celebrated grower-producers, producing just 13,000 bottles from a 2.2-hectare vineyard he inherited from his grandmother in 1987. Although his wines are in high demand and sell for respectable prices worldwide, such a small production may have proven insufficient to sustain his livelihood. In 2017, frost wiped out 80 per cent of his harvest, and he relinquished his grower-producer credentials to be reincarnated as a négociant in order to purchase fruit and grow his production.

More and more of Champagne’s most celebrated growers are following suit, though not all for the same reason. The acclaimed 9.5-hectare estate of Bérêche et Fils recently joined the négociant world, to create the flexibility not only to buy from growers but, surprisingly, to purchase more vineyards.

For the De Sousa family in the fabled grand cru of Avize, the decision to become a négociant came for a very different reason: France’s taxation system. As third-generation grower Erick De Sousa prepared to pass the estate on to his three children, he was faced with the realities of the country’s inheritance tax—a threat more crippling than global economics and climate change.

In France, children are stung with a 45 per cent inheritance tax—one of the highest taxes of its kind in the world. A generation ago it was possible to pay off inheritance tax in a single harvest. Today, Champagne is the highest-value appellation viticultural land on earth, and its top grand crus are now fetching up to €3m (AU$5m) per hectare. The vineyards and bottles of the little family estate of De Sousa alone must be worth well in excess of €30m. It would take a lifetime to pay off the tax on such an inheritance. The more than slightly ironic twist of switching from grower to négociant thus proved the only way to uphold the business in the family name.

We are now at a critical juncture in the evolution of the Champagne grower-producer.

The years to come will no doubt see more growers adapt and transition their businesses. But, while many smaller and less-recognised estates will return to selling their fruit to négociants, Dominique Demarville predicts that top growers like Egly-Ouriet—widely considered Champagne’s top grower—will flourish.

Francis Egly (of Egly-Ouriet) says the quality expected from grower-producer cuvées will drive the market. “In the past it was very easy for small producers to sell champagne, but today, a lot have trouble finding their place in the market,” he says. “The new generation of champagne lovers expect very good quality from small producers, and those who make mediocre quality will find it increasingly difficult to sell their production.”

Of course, this is not the worst thing. It would be no catastrophe for Champagne’s lesser growers to redirect their fruit to the négociant houses, shoring up overall supply while sustaining the livelihoods of more growers, with market prices incentivising better farming. And there is no doubt that the very best grower-producers, well established and well-loved across the champagne domain, will continue, against all odds, to strengthen their rightful place among the great wine estates of the world.